|

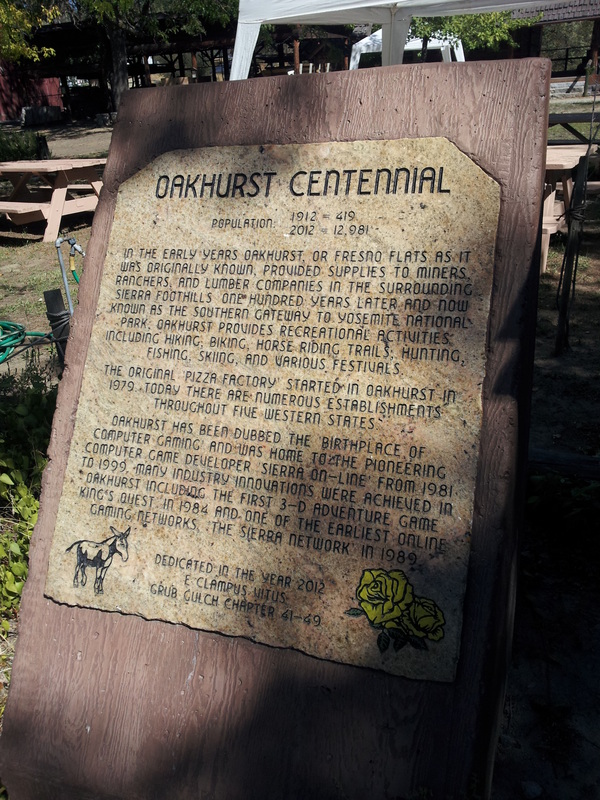

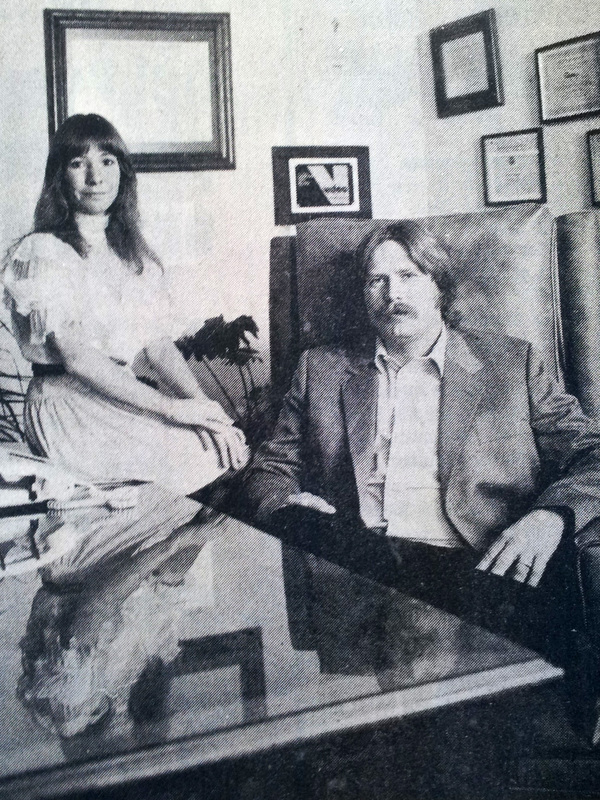

To celebrate the submission of my dissertation to my committee, I am posting an excerpt from the first chapter. I hope those of you who have followed my progress on social media or IRL enjoy this teaser for the project. I look forward to sharing more of it in the future. -Laine Chapter One: Emergences “In some adventures you are limited by the number of objects you can carry at one time. When it comes to a decision as to whether you should keep carrying an object that you already used, or drop it so you can get a new one, I would be inclined to drop it in order to be able to carry a new one.” —Roberta Williams “Winning Strategies for Adventures” The On-Line Letter, June 1981 Late in the summer of 2013, I traveled to Coarsegold and Oakhurst, California, a pair of towns separated by a seven-mile band of asphalt marked State Route 41, tucked away in the foothills of Madera County along the southern border of Yosemite National Park. On the last day of my trip, I drove out to Oakhurst's Fresno Flats Historic Park, a community heritage site established in 1975 in homage to the area's nineteenth-century Gold Rush roots. In a landscape rife with salt-of-the-earth history, these sorts of regional memorials dot and fleck every one-stoplight town along the highway. Most of them were founded in the 1970s and '80s, the boom years of civic pride in Madera County, when the middle-aged grandchildren of gold panners and loggers began gathering oral histories and commemorating landmarks. Yet, by 2013, these locales were mostly forgotten, the stuff of grade-school field trips and the occasional wedding reception. Those who had long served as the guardians of small-town memory, the founders of these dusty parks and ramshackle museums, were all thirty or forty years older now, their bodies too broken down to continue necessary repairs, their hands shaking and shivering as they leafed through archival documents, their memories shot through with forgetting. The Fresno Flats Historic Park's docents and guided tours had long since dried up; only a “caretaker” resided on premises during daylight hours, an old-timer sitting in an air-conditioned cabin who could hand you a pamphlet or give you directions. Mostly, I just saw people stop by to use the park's unlocked bathrooms. But if there was no docent to play warder to this park, to ensure I wasn't trying to jimmy my way across every locked door and sagging chain-link fence (which I certainly was), I did have to confront a very different kind of gatekeeper. A centennial plaque held empty court on the central axis of the park's sunburnt grassy entrance—what I suspected was faux marble mounted on faux wood. Dedicated by E Clampus Vitus, a regional fraternal order once founded to care for miners' widows, the plaque iterated Oakhurst, California's most defining testaments to national significance over the past hundred years. Most prominently, the town held a key location on the supply trails that once siphoned tools, liquor, and mules up to the northern gold mines and lumber sites leading in and out of Yosemite; second, Oakhurst was the founding location of Pizza Factory, a restaurant franchise boasting over one hundred establishments in five Western states; and lastly, the plaque dubbed Oakhurst “the birthplace of computer gaming.” Through the 1980s and '90s, Oakhurst and the smaller town Coarsegold had been home to Sierra On-Line, one of the most iconic and successful home computer entertainment software producers in the world. Co-founded by a curious husband-and-wife pair, Ken and Roberta Williams, Sierra found its fortune mostly in designing and distributing graphical adventure game software for the home computer market. Sierra would become one of the town's largest employers, alongside the Sierra-Tel telephone company and the county government. Up until the early 1990s, every box, every disk, every package was printed, formatted, and shrink-wrapped right in Oakhurst by the hands of self-declared “mountain folk.” Sierra On-Line was the reason I had traveled three thousand miles from New York City to get sunburnt and dehydrated twenty-two hundred feet above sea level. I'd come to this countryside to ask a question: what is video game history? Answers shift. In Coarsegold and Oakhurst, it seemed something best forgotten. There had been a soft promise, nearly thirty-five years ago, that a company like Sierra On-Line could turn the economic sinkhole of Madera County into a “Little Silicon Valley.” When Sierra moved most of its corporate operations to Bellevue, Washington in 1993, it left behind disgruntled memory and boundless rumor: Sierra had left because corporate taxes were too high, because they couldn't get a T1 line strung into Oakhurst, because relations were amiss at the top of the company chain. Double damage came in the late 1990s when the company was shuttered for good, closing up its remaining Oakhurst offices. After that, Sierra On-Line was just someone’s last paycheck. Yet, to the now-adult fans who teethed on Sierra's software in the 1980s and '90s, the company's material remnants—folded and boxed and sleeved by local labor but shipped to an audience worldwide—are objects to save, collect, cherish. These childhood memories are for sharing and endless reiteration. And there are other bodies, spaces, things. To the women of today's indie game scene, there's the hope of finding a history in Roberta Williams that reflects the history they lived but no one seems aware of—that, yes, women have always played games, and made them too. In the archives of the Strong Museum of Play, video game history is the mundane artefacts that clutter acid-free boxes: nameplates and buttons and broken awards. To the designers and employees I interview, it's a curiosity about why I care. It's a question of how long a floppy disk can hold its data before bit rot eradicates magnetic trace, and about how long Yosemite’s Half Dome will stand, a reminder of the thick temporality of stone. While the realm of armchair historians and amateur preservationists may swear to a video game history circumscribed by a heroic chronology of hacker heroes and coding wizards, “seminal games” and groundbreaking companies, tracking and tracing Sierra 'cross fields archival and literal has only confirmed to me the articulate queerness of our historical desires, of what we want history to do for us. The question of “what game history is” finds its answer in the doing, as this project is one that will take shape in the cluttered valley between history and historiography. The writing of video game history, despite its many participants, has been a fairly narrow field of action landmarked by a handful of monuments: Pong and the Magnavox Odyssey, Mario and Pac-Man, the alien death romps of Doom, the mesmerizing landscapes of Myst. Goldeneye, Grand Theft Auto, Wii Tennis. The ruins are real, and their importance inestimable—but they also cast shadows. In marking the map, they make it, they become what game history has been organized to show us. No book of video game history ever told me that Oakhurst, California was the “birthplace of computer gaming.” It probably is not. But what does that physical memorial make available to me, which I otherwise might not notice?

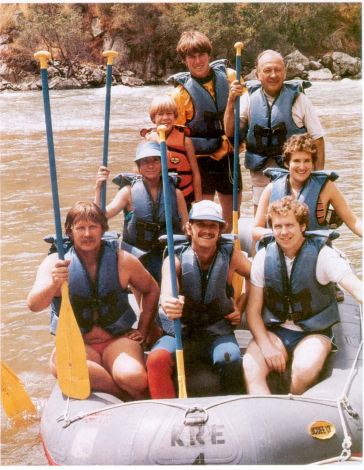

I believe: Sierra On-Line is the case that makes a mess of video game history. It makes good on Foucault's promise that “what is found at the historical beginning of things is not the inviolable identity of their origin; it is the dissension of other things. It is disparity.” My work herein is a media archaeological pressuring of several historiographic devices governing the structure and arc of what is taken as video game history. Articulating sites of disparity is a critically overdue maneuver in the unfolding historiography of the video game, a gesture countering the obviously problematic teleologics of much writing in the field. And it is a move that scales nicely beyond itself, to all the reasons video games are not just one component of a digital media landscape, but a condensation of digital media's most significant cultural and theoretical properties, from labor to materiality to transnationalist flows, global economics and mobile ubiquity to representation and virtual identity, down to design, distribution, the evils of e-waste. These are all part of a use-cycle of the global video game industry, a multiplicity which has no monolithic center, no representative feature, especially not once we formulate on planet-wide scales. Gaming is the first form of computational technology most of us ever handled—the first time, in many cases, a computer was ever “in our hands.” The level of convergence games enact with other media is a phenomena unto itself: games are constrained by no essential medium of transmission or reception, and can operate across digital and analog substrates. Games are neither experimental novelties nor thin amusements: they are definitive modes of mediation in the twenty-first century. The value of studying video game history should not be that it leads us back to games, but that it leads us somewhere else.  Raiford Guins discussing his time on-site at the Atari landfill in Alamogordo, NM. Raiford Guins discussing his time on-site at the Atari landfill in Alamogordo, NM. Back in May, Babycastles Gallery was generous enough to host a book launch I organized for Raiford Guins' Game After: A Cultural Study of Video Game Afterlife. After a warm welcome from Babycastle co-founder Kunal Gupta, Raiford gave a short reading followed by a presentation of his experience on-site at the Atari Landfill excavation this past April. He really, really loved that hard hat. Ray gave a great talk to a diverse audience of game designers, scholars, students and games enthusiasts. We enjoyed refreshments, music and an indie games installation in Babycastles gritty and beautiful DIY space. I've also learned that many major life events can benefit from customized balloons. Many thanks to the Babycastles team for pulling together (especially Syed and Kunal), and thank you to everyone who came! Props to the Stony Brook University Department of Cultural Analysis and Theory for funding the balloons. Enjoy these photos by Emi Spicer. Perhaps we wouldn't have expected Indiecade East's closing keynote on history, inclusion and indie-ness to come from Bennett Foddy. As a designer, Foddy is known for crushingly absurdist creations that frequently leave players alienated and confused; gameplay cramps the hand, rather than holding it. Yet Foddy's Sunday afternoon “State of the Union,” which served as a capstone to the entire weekend, was a thoughtful, accessible piece of work that embraced the many fractures some might claim are otherwise splitting apart the indie game world. Directly addressing Edmund McMillan's lament that “[the indie scene] use to feel very united but now feels very segregated,” Foddy argued that contemporary anxiety about the indie scene’s waning glory is largely a product of poor historical literacy on the part of the scene as a whole. In Foddy’s alternate timeline, the attributes we apply to “indie” production are nothing new—including accessible tools, self-distribution, superstar success narratives, and aesthetic or mechanic experimentation. These qualities didn't emerge fully-formed from the brains of the indie upper crust, like some digital Athena escaping from the head of Zeus. In most cases, they have existed within video game history since at least the early 1980s, if not earlier. Having established that the “indie” has always been there, Foddy suggested that what is truly unique to the now isn’t the “newness” of indie games at all (which is the mythology of a few elite indie devs). Rather, it is the baffling diversity of indie games, the reality that indie creation is more mechanically, representationally, and developmentally expansive than in any prior moment in video game history. For Foddy, the dream of a unified scene is an elitist one; what McMillan framed as segregation, Foddy spun as proliferation. As Foddy told it, video games are always already indie, and a word shouldn't be getting in the way of celebrating everything the indie movement has to offer. Foddy's larger cultural and inspirational goals are well taken. In gesturing for a historically-based notion of inclusivity, Foddy successfully countered the idea that the indie is a radical break in how we produce and experience games. By that logic, we should be much more open and accommodating of what McMillan experiences as “segregation.” But the successes of Foddy's talk came at the cost of a different kind of historical “accuracy”—our capacity to make conceptual and historically meaningful distinctions between two separate but often conflated cultural phenomena within game production: the independent and the indie. I borrow this handy distinction from scholars Maria B. Garda and Pawel Grabarczyk. In Garda and Grabarczyk's classification, independent may apply to work that is “financially” independent (non-AAA), or stylistically independent (non-mainstream). Indie, however, is a movement that emerged at the turn of the 21st century. Additionally, indie is also sometimes a genre or marketing tag tied to this movement. In the history Foddy wove, there was no distinction between these two very different categories. When Foddy cited the “indieness” of Commander Keen or Lemmings or the Scandinavian demoscene, he was often referring to their “independent” status. While my point may seem like a ponderous subtlety, conflating these ideas actually produces different kinds of histories—which in turn, affects how we experience our emotional relationship to the past. To follow Foddy's argument, McMillan's lack of historical awareness in part produced his sense of entitlement and authority. Part of Foddy's work was to challenge the validity of that sensibility by offering a history-check of indie hubris. As someone interested in how we create safer spaces and more viable environments for all the bodies and persons who wish to participate in video game culture, I'm in sync with Foddy's intentions. But as a historian, I am equally suspect of reading the past in the terms of the present—what we call historical anachronism. While I'd be foolish to think that the distinction between “independent” and “indie” wasn't implicit for Foddy, I've run into more than one person who thought the takeaway was found in the historical merit of a “true” history of indie development. Case in point: Foddy began with the classic image of Spacewar!, and cleverly suggested that games have always sort of looked like crap—in other words, “been indie.” But this statement evaporates an enormously complex landscape of cultural, economic and technological factors. It should not go without notice that all of the ludo-computational experiments we absorb as part of “video game history” were produced by individuals with substantial means of income elsewhere: they were all men working in some form of military research or defense. This includes Steven “Slug” Russell's Spacewar!, as well as William Higinbotham's Tennis for Two, Will Crowther and Don Woods' Colossal Cave Adventure, the original PDP-10 instantiation of Zork produced by members of MIT's Dynamic Modeling Group, as well as countless games circulated through ARPANET and housed on research center and university mainframes. Were these games “indie?” Not at all. How could they be? They had nothing to be independent from.  Do not be fooled! These are not indie game designers. // Rafting trip group photo, circa 1981. Counterclockwise from left: Ken Williams, Gary Kofler of Sega, Doug Carlston, Judy Rabin, John Heuer (Roberta's father), the river guide, D.J. Williams (Ken and Roberta's son), Roberta Williams. Image from Sierra News Magazine, “An Excerpt From An Insider's Look at the Personal Computer Software Industry,” Spring 1990, 55. Image via Sierra Gamers, www.sierragamers.com. And even once there was an “industry” of which to speak, how various companies or game designers understood themselves as “independent” is a fluctuating category. As I explored in my own Indiecade East talk on the early 1980s West Coast microcomputer software scene, when companies like Broderbund, Sirius and On-Line Systems/Sierra On-Line called themselves “independent,” they meant independent from other computer manufacturers. Their corollary to Activision or Rockstar wasn't other game companies—it was hardware producers like IBM, who had the money and manpower to crush the cottage industry companies overnight.

What I'd like to see, as someone deeply engaged by the pasts always playing out in our present, is a more exacting assessment of the past's historical character. There are historical specifics that unite the examples Foddy brought before us to the conditions of the present, but they are not the one's he mentioned. If we want powerful and precise lessons from game history, we might think of them this way:

But this is not the same as saying video games have always been indie. The circumstances by which a game emerges outside of mass production or certain forms of capitalist exchange are unique to the economic and industrial character of its time. No matter how much value we take in seeing a reflection of our own practices in the past, and how much we might learn through these comparisons I always want to insist: history is not there for us. When we believe it is, we commit the McMillan fallacy—whether that's investing faith in the newness of the indie, or validating our work by tying it to a (politically and representationally fraught) past. And what of indie “as a movement”? As a subculture, reckoning with the gap between “the indie” and “the independent” can help those invested in the movement understand why there is so much strife around the term “indie” in the present: because we're all actually talking about different things. If there is anything remarkable about Indiecade, it is that it so clearly doesn't know where it is going, and thus, its net can still afford to be wide. What to make of a conference where witch poet gamecrafter Merritt Kopas performs Tarot, and Caspar Gray lectures on pitching games to the AAAs? We should think about Foddy's argument in the reverse: “indie” is the present-day coin of the realm, describing game production that meets the qualifications of the two historical conditions I outlined above. Indie isn't something someone did or made or invented. “Indie” is a participant response, a mode of community organization and self-recognition, rather than a transhistorical schematic for understanding the history of games. “Indie” is a referent for a curious balancing act between art and business, commerce and creativity, one made possible by very specific technological affordances, the economic operations of late capitalism, varied aesthetic imperatives about the contours of “personal expression,” a kind of neoliberal hucksterism around the power of individual creativity, and the endlessly scalable conditions which drive our creative desires. Indie is indie because it is now, because it is meaningful in the present, because through some strange confluence of economic, technological and cultural conditions, people became invested in identifying themselves in this way—this is what is unique to indie games today, a historically-specific truth not shared with any past example of marginal game production. Acknowledgements I'd like to thank Colin Snyder, Ida C. Benedetto and Bennett Foddy for being my mental scratchpad as I worked through these ideas. |

Archives

March 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed