|

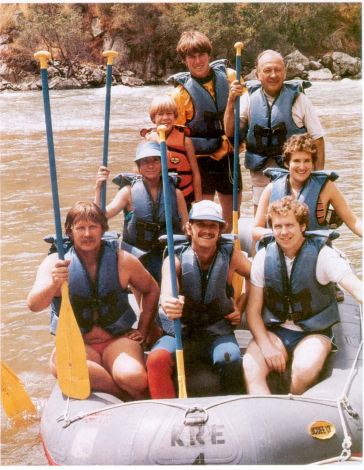

Perhaps we wouldn't have expected Indiecade East's closing keynote on history, inclusion and indie-ness to come from Bennett Foddy. As a designer, Foddy is known for crushingly absurdist creations that frequently leave players alienated and confused; gameplay cramps the hand, rather than holding it. Yet Foddy's Sunday afternoon “State of the Union,” which served as a capstone to the entire weekend, was a thoughtful, accessible piece of work that embraced the many fractures some might claim are otherwise splitting apart the indie game world. Directly addressing Edmund McMillan's lament that “[the indie scene] use to feel very united but now feels very segregated,” Foddy argued that contemporary anxiety about the indie scene’s waning glory is largely a product of poor historical literacy on the part of the scene as a whole. In Foddy’s alternate timeline, the attributes we apply to “indie” production are nothing new—including accessible tools, self-distribution, superstar success narratives, and aesthetic or mechanic experimentation. These qualities didn't emerge fully-formed from the brains of the indie upper crust, like some digital Athena escaping from the head of Zeus. In most cases, they have existed within video game history since at least the early 1980s, if not earlier. Having established that the “indie” has always been there, Foddy suggested that what is truly unique to the now isn’t the “newness” of indie games at all (which is the mythology of a few elite indie devs). Rather, it is the baffling diversity of indie games, the reality that indie creation is more mechanically, representationally, and developmentally expansive than in any prior moment in video game history. For Foddy, the dream of a unified scene is an elitist one; what McMillan framed as segregation, Foddy spun as proliferation. As Foddy told it, video games are always already indie, and a word shouldn't be getting in the way of celebrating everything the indie movement has to offer. Foddy's larger cultural and inspirational goals are well taken. In gesturing for a historically-based notion of inclusivity, Foddy successfully countered the idea that the indie is a radical break in how we produce and experience games. By that logic, we should be much more open and accommodating of what McMillan experiences as “segregation.” But the successes of Foddy's talk came at the cost of a different kind of historical “accuracy”—our capacity to make conceptual and historically meaningful distinctions between two separate but often conflated cultural phenomena within game production: the independent and the indie. I borrow this handy distinction from scholars Maria B. Garda and Pawel Grabarczyk. In Garda and Grabarczyk's classification, independent may apply to work that is “financially” independent (non-AAA), or stylistically independent (non-mainstream). Indie, however, is a movement that emerged at the turn of the 21st century. Additionally, indie is also sometimes a genre or marketing tag tied to this movement. In the history Foddy wove, there was no distinction between these two very different categories. When Foddy cited the “indieness” of Commander Keen or Lemmings or the Scandinavian demoscene, he was often referring to their “independent” status. While my point may seem like a ponderous subtlety, conflating these ideas actually produces different kinds of histories—which in turn, affects how we experience our emotional relationship to the past. To follow Foddy's argument, McMillan's lack of historical awareness in part produced his sense of entitlement and authority. Part of Foddy's work was to challenge the validity of that sensibility by offering a history-check of indie hubris. As someone interested in how we create safer spaces and more viable environments for all the bodies and persons who wish to participate in video game culture, I'm in sync with Foddy's intentions. But as a historian, I am equally suspect of reading the past in the terms of the present—what we call historical anachronism. While I'd be foolish to think that the distinction between “independent” and “indie” wasn't implicit for Foddy, I've run into more than one person who thought the takeaway was found in the historical merit of a “true” history of indie development. Case in point: Foddy began with the classic image of Spacewar!, and cleverly suggested that games have always sort of looked like crap—in other words, “been indie.” But this statement evaporates an enormously complex landscape of cultural, economic and technological factors. It should not go without notice that all of the ludo-computational experiments we absorb as part of “video game history” were produced by individuals with substantial means of income elsewhere: they were all men working in some form of military research or defense. This includes Steven “Slug” Russell's Spacewar!, as well as William Higinbotham's Tennis for Two, Will Crowther and Don Woods' Colossal Cave Adventure, the original PDP-10 instantiation of Zork produced by members of MIT's Dynamic Modeling Group, as well as countless games circulated through ARPANET and housed on research center and university mainframes. Were these games “indie?” Not at all. How could they be? They had nothing to be independent from.  Do not be fooled! These are not indie game designers. // Rafting trip group photo, circa 1981. Counterclockwise from left: Ken Williams, Gary Kofler of Sega, Doug Carlston, Judy Rabin, John Heuer (Roberta's father), the river guide, D.J. Williams (Ken and Roberta's son), Roberta Williams. Image from Sierra News Magazine, “An Excerpt From An Insider's Look at the Personal Computer Software Industry,” Spring 1990, 55. Image via Sierra Gamers, www.sierragamers.com. And even once there was an “industry” of which to speak, how various companies or game designers understood themselves as “independent” is a fluctuating category. As I explored in my own Indiecade East talk on the early 1980s West Coast microcomputer software scene, when companies like Broderbund, Sirius and On-Line Systems/Sierra On-Line called themselves “independent,” they meant independent from other computer manufacturers. Their corollary to Activision or Rockstar wasn't other game companies—it was hardware producers like IBM, who had the money and manpower to crush the cottage industry companies overnight.

What I'd like to see, as someone deeply engaged by the pasts always playing out in our present, is a more exacting assessment of the past's historical character. There are historical specifics that unite the examples Foddy brought before us to the conditions of the present, but they are not the one's he mentioned. If we want powerful and precise lessons from game history, we might think of them this way:

But this is not the same as saying video games have always been indie. The circumstances by which a game emerges outside of mass production or certain forms of capitalist exchange are unique to the economic and industrial character of its time. No matter how much value we take in seeing a reflection of our own practices in the past, and how much we might learn through these comparisons I always want to insist: history is not there for us. When we believe it is, we commit the McMillan fallacy—whether that's investing faith in the newness of the indie, or validating our work by tying it to a (politically and representationally fraught) past. And what of indie “as a movement”? As a subculture, reckoning with the gap between “the indie” and “the independent” can help those invested in the movement understand why there is so much strife around the term “indie” in the present: because we're all actually talking about different things. If there is anything remarkable about Indiecade, it is that it so clearly doesn't know where it is going, and thus, its net can still afford to be wide. What to make of a conference where witch poet gamecrafter Merritt Kopas performs Tarot, and Caspar Gray lectures on pitching games to the AAAs? We should think about Foddy's argument in the reverse: “indie” is the present-day coin of the realm, describing game production that meets the qualifications of the two historical conditions I outlined above. Indie isn't something someone did or made or invented. “Indie” is a participant response, a mode of community organization and self-recognition, rather than a transhistorical schematic for understanding the history of games. “Indie” is a referent for a curious balancing act between art and business, commerce and creativity, one made possible by very specific technological affordances, the economic operations of late capitalism, varied aesthetic imperatives about the contours of “personal expression,” a kind of neoliberal hucksterism around the power of individual creativity, and the endlessly scalable conditions which drive our creative desires. Indie is indie because it is now, because it is meaningful in the present, because through some strange confluence of economic, technological and cultural conditions, people became invested in identifying themselves in this way—this is what is unique to indie games today, a historically-specific truth not shared with any past example of marginal game production. Acknowledgements I'd like to thank Colin Snyder, Ida C. Benedetto and Bennett Foddy for being my mental scratchpad as I worked through these ideas.

Kevin Cancienne

6/23/2014 07:29:23 am

Laine, this is good.

Laine Nooney

7/2/2014 05:34:20 am

Thanks Kevin! So many props to you and Margaret for such a great event.

This is excellent. I hadn't encountered Foddy's talk, and, like you, really like his idea of framing the expansion of the independent games scene as proliferation, not segregation.

Laine Nooney

7/2/2014 05:44:08 am

Hi Joseph, Comments are closed.

|

Archives

March 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed