|

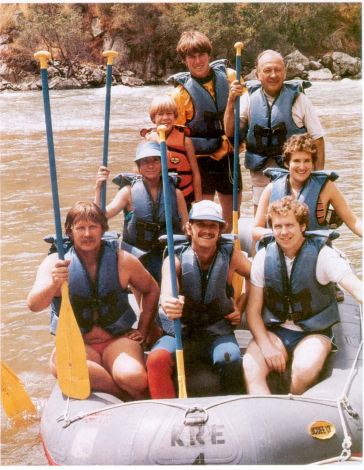

Perhaps we wouldn't have expected Indiecade East's closing keynote on history, inclusion and indie-ness to come from Bennett Foddy. As a designer, Foddy is known for crushingly absurdist creations that frequently leave players alienated and confused; gameplay cramps the hand, rather than holding it. Yet Foddy's Sunday afternoon “State of the Union,” which served as a capstone to the entire weekend, was a thoughtful, accessible piece of work that embraced the many fractures some might claim are otherwise splitting apart the indie game world. Directly addressing Edmund McMillan's lament that “[the indie scene] use to feel very united but now feels very segregated,” Foddy argued that contemporary anxiety about the indie scene’s waning glory is largely a product of poor historical literacy on the part of the scene as a whole. In Foddy’s alternate timeline, the attributes we apply to “indie” production are nothing new—including accessible tools, self-distribution, superstar success narratives, and aesthetic or mechanic experimentation. These qualities didn't emerge fully-formed from the brains of the indie upper crust, like some digital Athena escaping from the head of Zeus. In most cases, they have existed within video game history since at least the early 1980s, if not earlier. Having established that the “indie” has always been there, Foddy suggested that what is truly unique to the now isn’t the “newness” of indie games at all (which is the mythology of a few elite indie devs). Rather, it is the baffling diversity of indie games, the reality that indie creation is more mechanically, representationally, and developmentally expansive than in any prior moment in video game history. For Foddy, the dream of a unified scene is an elitist one; what McMillan framed as segregation, Foddy spun as proliferation. As Foddy told it, video games are always already indie, and a word shouldn't be getting in the way of celebrating everything the indie movement has to offer. Foddy's larger cultural and inspirational goals are well taken. In gesturing for a historically-based notion of inclusivity, Foddy successfully countered the idea that the indie is a radical break in how we produce and experience games. By that logic, we should be much more open and accommodating of what McMillan experiences as “segregation.” But the successes of Foddy's talk came at the cost of a different kind of historical “accuracy”—our capacity to make conceptual and historically meaningful distinctions between two separate but often conflated cultural phenomena within game production: the independent and the indie. I borrow this handy distinction from scholars Maria B. Garda and Pawel Grabarczyk. In Garda and Grabarczyk's classification, independent may apply to work that is “financially” independent (non-AAA), or stylistically independent (non-mainstream). Indie, however, is a movement that emerged at the turn of the 21st century. Additionally, indie is also sometimes a genre or marketing tag tied to this movement. In the history Foddy wove, there was no distinction between these two very different categories. When Foddy cited the “indieness” of Commander Keen or Lemmings or the Scandinavian demoscene, he was often referring to their “independent” status. While my point may seem like a ponderous subtlety, conflating these ideas actually produces different kinds of histories—which in turn, affects how we experience our emotional relationship to the past. To follow Foddy's argument, McMillan's lack of historical awareness in part produced his sense of entitlement and authority. Part of Foddy's work was to challenge the validity of that sensibility by offering a history-check of indie hubris. As someone interested in how we create safer spaces and more viable environments for all the bodies and persons who wish to participate in video game culture, I'm in sync with Foddy's intentions. But as a historian, I am equally suspect of reading the past in the terms of the present—what we call historical anachronism. While I'd be foolish to think that the distinction between “independent” and “indie” wasn't implicit for Foddy, I've run into more than one person who thought the takeaway was found in the historical merit of a “true” history of indie development. Case in point: Foddy began with the classic image of Spacewar!, and cleverly suggested that games have always sort of looked like crap—in other words, “been indie.” But this statement evaporates an enormously complex landscape of cultural, economic and technological factors. It should not go without notice that all of the ludo-computational experiments we absorb as part of “video game history” were produced by individuals with substantial means of income elsewhere: they were all men working in some form of military research or defense. This includes Steven “Slug” Russell's Spacewar!, as well as William Higinbotham's Tennis for Two, Will Crowther and Don Woods' Colossal Cave Adventure, the original PDP-10 instantiation of Zork produced by members of MIT's Dynamic Modeling Group, as well as countless games circulated through ARPANET and housed on research center and university mainframes. Were these games “indie?” Not at all. How could they be? They had nothing to be independent from.  Do not be fooled! These are not indie game designers. // Rafting trip group photo, circa 1981. Counterclockwise from left: Ken Williams, Gary Kofler of Sega, Doug Carlston, Judy Rabin, John Heuer (Roberta's father), the river guide, D.J. Williams (Ken and Roberta's son), Roberta Williams. Image from Sierra News Magazine, “An Excerpt From An Insider's Look at the Personal Computer Software Industry,” Spring 1990, 55. Image via Sierra Gamers, www.sierragamers.com. And even once there was an “industry” of which to speak, how various companies or game designers understood themselves as “independent” is a fluctuating category. As I explored in my own Indiecade East talk on the early 1980s West Coast microcomputer software scene, when companies like Broderbund, Sirius and On-Line Systems/Sierra On-Line called themselves “independent,” they meant independent from other computer manufacturers. Their corollary to Activision or Rockstar wasn't other game companies—it was hardware producers like IBM, who had the money and manpower to crush the cottage industry companies overnight.

What I'd like to see, as someone deeply engaged by the pasts always playing out in our present, is a more exacting assessment of the past's historical character. There are historical specifics that unite the examples Foddy brought before us to the conditions of the present, but they are not the one's he mentioned. If we want powerful and precise lessons from game history, we might think of them this way:

But this is not the same as saying video games have always been indie. The circumstances by which a game emerges outside of mass production or certain forms of capitalist exchange are unique to the economic and industrial character of its time. No matter how much value we take in seeing a reflection of our own practices in the past, and how much we might learn through these comparisons I always want to insist: history is not there for us. When we believe it is, we commit the McMillan fallacy—whether that's investing faith in the newness of the indie, or validating our work by tying it to a (politically and representationally fraught) past. And what of indie “as a movement”? As a subculture, reckoning with the gap between “the indie” and “the independent” can help those invested in the movement understand why there is so much strife around the term “indie” in the present: because we're all actually talking about different things. If there is anything remarkable about Indiecade, it is that it so clearly doesn't know where it is going, and thus, its net can still afford to be wide. What to make of a conference where witch poet gamecrafter Merritt Kopas performs Tarot, and Caspar Gray lectures on pitching games to the AAAs? We should think about Foddy's argument in the reverse: “indie” is the present-day coin of the realm, describing game production that meets the qualifications of the two historical conditions I outlined above. Indie isn't something someone did or made or invented. “Indie” is a participant response, a mode of community organization and self-recognition, rather than a transhistorical schematic for understanding the history of games. “Indie” is a referent for a curious balancing act between art and business, commerce and creativity, one made possible by very specific technological affordances, the economic operations of late capitalism, varied aesthetic imperatives about the contours of “personal expression,” a kind of neoliberal hucksterism around the power of individual creativity, and the endlessly scalable conditions which drive our creative desires. Indie is indie because it is now, because it is meaningful in the present, because through some strange confluence of economic, technological and cultural conditions, people became invested in identifying themselves in this way—this is what is unique to indie games today, a historically-specific truth not shared with any past example of marginal game production. Acknowledgements I'd like to thank Colin Snyder, Ida C. Benedetto and Bennett Foddy for being my mental scratchpad as I worked through these ideas. Today I'm posting the press release for a great project being co-piloted by my colleague at Illinois Institute of Technology, Carly Kocurek. So, aside from being a great game historian, Kocurek's also breaking into the realm of game design--a move I'm glad to see more and more game academics make. Read through the press release for this provocative game, and donate something if you can. We need a game world with more options like these. "Choice: Texas" // An IndieGoGo Campaign Launch Game addresses reproductive healthcare access in the Lone Star State

PRESS RELEASE: Austin (August 19, 2013) – Choice: Texas, an interactive fiction game addressing abortion access in Texas, officially launches its IndieGoGo fundraising campaign on August 19, 2013 (http://www.indiegogo.com/projects/choice-texas-a-very-serious-game/x/3912619). Billed as “a very serious game,” Choice: Texas draws on research into Texas legal regulations, geography, and demographics and asks players to consider the plight of women seeking reproductive healthcare in the lone star state. Funds raised through the campaign will assist in game development and publicity. “This game is about an important issue effecting women in Texas, and is intended as a means of furthering discussion and empathy,“ said game co-developer and co-designer Carly Kocurek. “We really think games can facilitate further conversation about and understanding of these kinds of issues.” The game, developed and designed by Kocurek and Allyson Whipple, invites players to experience the story of one of several Texas women, ranging from a high school honors student not ready to be a mother to an excited mother-to-be confronted with dangerous medical complications. While the women are fictional, they are reflective of Texas’s population and the regulations, financial barriers, and geographic limitations faced by the characters are also drawn from the state’s real environment. A prototype of the game will be presented at the Future and Reality of Gaming (FROG) 13 conference in Vienna this fall, and a complete version of the game will be published as a browser game in January 2014. The game will be free to play, and will feature original artwork by illustrator Grace Jennings. Fundraising for the game will be open through September 15, 2013. Further information about the game is available on the game’s Tumblr, at choicetexas.tumblr.com. Kocurek and Whipple are both available for interviews, and can be contacted by e-mail at [email protected] or via phone at (940) 224-2235. A Thoughtful Farewell, or, What Different Games Taught Me about Inclusive Conference Design7/18/2013

The Future of Different Games, and a Personal Farewell If you've followed me on Twitter or this blog, you've seen what a marvel Different Games has been. It created a much needed spaciousness within the game scene, and helped activate a community that otherwise was operating in small cohorts or latent networks. Personally and professionally, Different Games galvanized my commitment to tactics of public engagement that can move me beyond the bulwark of a department or a university. Gaming, game design and game communities can benefit from critical discourses, but these must be able to successfully code switch between specialist and populist languages. Having a Ph.D. isn't enough to ensure one is translatable in this regard—more often than not, it's an active impediment. Different Games was my crash course language exam in navigating the indie game scene. Many have asked if Different Games will happen again. I am thrilled to say that it will. However, my pride and happiness in the continuation of this conference is only matched by my sadness in announcing that this project must move on without me. This wasn't a decision I made lightly—but it I also wouldn't have made it if I didn't find it to be an absolute necessity for my continued success. And this was a decision that my co-organizer and I, Sarah Schoemann, came to agreement on, based on the tumultuous turns our lives were taking. Sarah is heading down to Georgia Tech later this summer, to begin her Ph.D., and whole exciting new phase of her academic life. Meanwhile, this is the year I finish my dissertation, send out cover letters, and try my hand at academia's very own craps table, the academic job market. I want—and expect—a lot out of this career. In stepping down from organizing Different Games, I am committing myself to focus on landing somewhere that fulfills my desires for intellectual community, resource support, and research flexibility. Furthermore, my experiences with Different Games has provided the friction necessary to generate my own luminous dreams—I'm stewing on how to pull off the “Different Games” of game history. Different Games gave me the best possible gift: the initiative and confidence to chase after new personal wins. And I'm grateful in knowing that whatever I build will always be in conversation with the team Sarah leads to produce Different Games. Reflections on Inclusive Conference Design In honoring my time with Different Games, I can recognize lessons learned that changed my relationship to event organization and conference planning. In a spirit fitting of Different Games, I want to use the second half of this blog post to create a reflection and resource on what Different Games taught me about inclusive conference design. With the experience of running Different Games under my belt, I know I don't have to ever accept claims that the underrepresentation of women, racial and ethnic minorities, or other marginalized identity categories at academic or mixed discipline conferences are just “how it is” or “the best we can do.” If you have aspirations for throwing inclusive and diverse events, this is absolutely the best advice I can give you, learned 100% in the doing.

1. Politics of inclusion have to be built in from the start Diversity is not an ingredient. It is not something you reach for to mix “marginal voices” into an otherwise homogenous scene. Example: if you throw a conference with an all white male planning committee, it may not matter how sincerely “interested” in diversity you are. Consider instead: does an event with such an structure come off as a safe space for diverse participants? Does it seem aware of itself and capable of holding an inclusive space? Are members of this group trusted by those you seek to participate (see #2)? This is not to say that a homogenous planning committee cannot attune themselves to these issues (or that it will not, in and of itself, contain diverse backgrounds, experiences and identity categories). But casting a broader net involves cultivating an attitude about accessibility, not simply a desire for addition. For example, when planning of Different Games, Sarah and I discussed early on our own representational positions, and their limits. While we felt positive as two queer/queer-allied women planning this conference, we talked about ourselves as both white, abled women, with class and educational privilege. We had to be comfortable discussing these vectors from the outset, because they were critical to refining our language and developing trust with the community to which we were attending. This is why I have at times responded negatively to requests from other conferences to simply “use” or “borrow” our inclusivity statement—because if you don't do that processing and critical thinking amongst your own team, you will not be able to effectively express it to participants. Events also need to be sensitive to issues around intellectual inclusion—if you intend on throwing a mixed-discipline event, you must build in submission and evaluation systems that are flexible to different professional standards of genre writing, intellectual “rigor” and creative endeavor. 2. Disparities in participation are network problems, not knowledge problems The people are always out there. They may not be what you expect. They may not come with typical pedigrees. But smart, interesting people of diverse backgrounds and subjectivities are doing great work in the world. If your event receives a low level of participation from a desired group, the problem isn't “them.” It's you. To hide behind claims of the “male dominated” character of a scene, or to claim that the problem will “correct itself” when “more 'X' individuals” are qualified to participate, is to misidentify one's own structural participation in the problem. It is to treat a network problem (problems of social capital and community trust) as if it is an empirical knowledge problem (there just aren't enough “X” doing “Y”). Problems of visibility are structural—which means you have to position your project in such a way that it amplifies what a system is internally designed to shut down (this is why diversity as “add-in” can be a damaging move). So when you're thinking about inclusion and diverse participants, the question is: do you know where you are on their network? Are you even visible on their network? And if you want to be, how do you get visible on their network? These are concerns more about building trust and relating to a community than they are hitting a numbers game. In other words—if you don't know the vaguest contours of the people you're trying to reach (or people who know these people), you may not be the right person or group for the project. 3. Own, don't defend, what you cannot account for For all that you try to remain sensitive to and handle with consideration, you have the accept the embedded limitation of inclusivity: there is no way to get it “right.” Things will escape you. You won't be able to cover it all. Someone will critique your efforts. More people may not even recognize all the places you did succeed. What's important about these experiences and critiques is that you hear them and let yourself be shifted by them. You have to own your limitations are much as your success. For example: one of the big blindspots in the organization of Different Games was around ablist issues. This happened for reasons of time, attention, and personal and institutional bias. This came to our attention in several ways. A couple weeks before the conference, we were called out about having an entirely abled presenter line-up. We had to publicly own our limitation, and publicly acknowledge that we were aware of this and would like to endeavor to improve. At the conference itself, there was considerable tension around the use of the word “crazy,” which was a word specifically flagged in our inclusivity statement. When frustration around the use of this word originally arose on Twitter, all the work we'd done from the very beginning followed through for us. Sarah and I took it seriously. We discussed the issue with volunteers to get their perspectives. Sarah found it appropriate to make a public statement asking presenters to remain sensitive to language. We weren't able to “solve” the problem—but we were able to own the problem in a way that let other people know critical, serious reflection was welcome, and set a positive precedent for future events (read Alison Harvey's excellent, judicious write-up of the issues around ableist language at DG). Overall, what I learned from the DG experience is that how you handle what arises can matter more than what you're handling. The terms and languages of social experience are always shifting. Over time, margins can come to be acknowledged as new centers, and previously unaccounted for systemic disparities become more legible. Addressing problem through the hows rather than the whats cultivates an attitude that focuses on sustaining networks and connections and the pleasure of human interaction. It's an attitude that permits growing in all directions, rather than a narrow focus on certain types of (only ever historically-specific) categories. Thanks for reading. Thanks for supporting Different Games. Let's all keep being awesome to each other. --Laine |

Archives

March 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed