|

The History of Games International Conference 1st edition: Working With, Building, and Telling History Montreal, Canada. June 21st – 23rd 2013 Organizers: Espen Aarseth (IT University of Copenhagen), Raiford Guins (Stony Brook University), Henry Lowood (Stanford University), Carl Therrien (Université de Montréal) In spite of the strong wake of game studies in the last decade, the history of video and computer games is still in its infancy in the academic world. Some significant contributions have been made and continue to emerge. In order to make the most out of these contributions and to reflect on the methodological issues they raise, we have decided to create the first international conference on the history of games. This will be the occasion to bring together academics, curators and museum exhibitors, introduce the general public and students to the history of the medium, and sensitize partners from the game industry to their role in terms of cultural heritage and preservation.

We invite proposals on the history of games at large, as long as it is tied with the electro-mechanical / digital development of the phenomenon. Special attention should be given to the methodological issues raised by your historical research. The conference seeks original submissions from researchers interested in diverse areas of historical study including, but not limited to: social history, military history, cultural history, memory studies, sensory history, history of technology, history of play and games, history of computing, art history, material culture, historical archaeology, as well as historical preservation, library and information science, and museum studies. The conference will explore three main areas of historical research. We encourage contributors to work within one of the proposed tracks. Each track will be led by a keynote speaker to kick-off the discussions and debates:

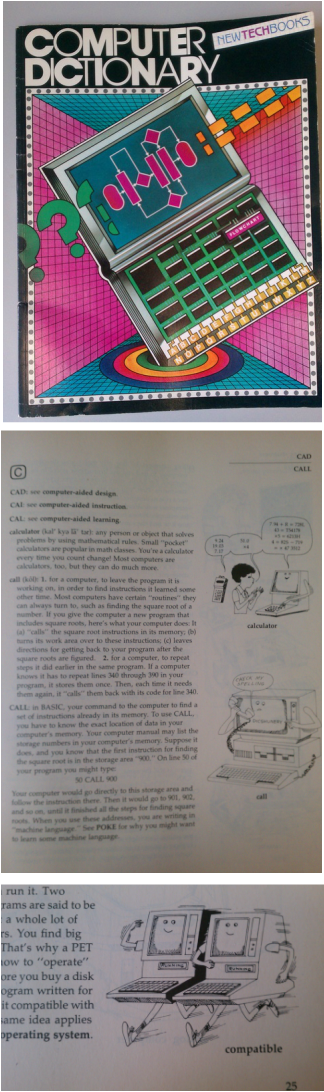

Submissions Proposals should be at least 1000 words in length (plus references) and include a title, author’s name, affiliation and short C.V., and provide a clear synopsis for a 20-minute conference length paper. Deadline for proposals: December 15th 2012. Please send proposals to Laine Nooney ([email protected]).  I came into campus today, and was pleased to see that my copy of Computer Dictionary had arrived. I'd stumbled upon this little object somewhere after a late night on the net; I was able to find a used bookstore with a copy to sell via Amazon. Computer Dictionary was published in 1984 by Scholastic Book Services (remember that beloved company that littered our grade school home rooms with tissue-y paper flyers full of cheaply produced paperbacks?). It retailed for $4.95, and does indeed seem to have been marketed to children (a claim I'm solely basing on the reference to "your teacher" on the first page). The premise of Computer Dictionary seems to be that contemporary dictionaries didn't included much of the new lingo attached to computing: "[...] terms you've never heard before keep popping up every few seconds. Pixel, LOGO, semiconductor. Some aren't even words! CP/M, DOS, PL1: It's like alphabet soup." The pages that follow are a bit more like an encyclopedia than a dictionary. Rather than providing just definitions, the book attempts to explain terms through examples geared to a middle-school reading level (making some of these definitions really confusing!). What I appreciate historically is this snapshot of an effort the make computers approachable to a lay audience. These sort of documents also provide valuable access to know what kind of words and concepts were in the popular discourse of computing during the early 1980s. Particularly exciting/hilarious are the illustrations paired with these terms. Great effort is made to anthropomorphize the computer through whatever means possible. The computers are frequently drawn with arms, legs and faces, and interact (talk, run, play) with humans and other machines. This, of course, is a common trope for representing objects to children: asking the child to relate to an object as an active, affective being rather than inert matter (of course this being is always the human being, rather than the object's being on its own terms). Computer Dictionary was authored by Patricia Conniffe. A less-than-rigorous Google search pulls up a little spat of these books that she authored or co-authored during the same time period, including "Word Processing", "Family Computing Dictionary of Computer Terms Made Simple", published in conjunction with Family Computing magazine, and "Activity Book for the Bank Street Writer". I'm curious to do some digging to see how similar the Family Computing Dictionary was to Computer Dictionary, since Family Computing magazine was also published by Scholastic. Family Computing magazine is a fascinating object in its own right (and one which will be getting plenty of dissertation attention, have no fear!), especially since its title transitioned several times, from Family Computing to "Family and Home Office Computing" to "Home Office Computing." Wikipedia has also pointed me to THIS amazing historical object, a clip from the Family Computing TV show spin-off that aired on Lifetime! For my Summer Session II class, I wanted to add a social media/microblogging component. I’d used my University’s Blackboard Wiki in a previous class, but found the whole thing badly-designed. I was determined to step up my game in terms of social media integration, so I decided to test-pilot Tumblr. Students were required to post two assignments on the class Tumblr, but were NOT required to use the site in any other capacity.

What Worked 1. Tumblr as the Class Commons Tumblr became the de-facto landing pad for my class. Since I was in a smart classroom, it was easy for me to pull up announcements, tips, reminders or examples that I’d posted since the previous class--I usually opened class with the Tumblr. As opposed to Blackboard, Tumblr was a clean and publically accessibly interface. When updating my lectures, I often found it easier to put images and clips up on Tumblr than to hassle with powerpoint, and I could throw up last minute examples as they came to mind late at night or during class break. I can’t speak to how this compares with something like WordPress (haven’t tried it), but I like the simplicity of Tumblr’s post-types, the ease of pulling content from the Tumblr community, and the fact that students would have to engage a bit with the online community of Tumblr. Our class Tumblr was like a little hub in a much larger hive. 2. My Students Surprised Me After I modeled the Tumblr as a place for posting class-relevant content, several students began using the Tumblr volitionally. They posted vids and images with a few keywords about how it might relate to the course, or linked to an example they brought up in class. When we went on a tour of the Met, students uploaded their cell phone snapshots, which enabled me to discuss works they liked by scrolling through the Tumblr. Naturally, some students participated more than others, but I’d say about 1/3-1/2 of the class used the Tumblr on their own, with no incentive. This was revealing, because several of my heaviest users were low-level in-class participators. The Tumblr became a space of serious engagement for those students who didn’t like to talk, and I was able to take that into account for participation grades. In short? They surprised me with their willingness to use the site, and the quality of the content they put there. What Didn’t Work (Or, Lessons Learned) 1. Make Them Members Because I didn’t go into the Tumblr with much of a “plan”, I fumbled a bit with how to manage a group of students on the site. First I made the site password protected, but some reported they couldn't access it with the password. I didn't have time to troubleshoot their problems individually, so I dropped that and tried to make them all become members, so they could access the Tumblr on their Dashboard. But then, because I’d also included a “submit content” option on the sidebar, some students decide to forgo setting up accounts and just submitted content that way. So I deleted members and let students just use the submit function. But the submit function isn’t as advanced as the Dashboard posting options, so there were inconsistencies that popped up which I still can’t explain: some students were able to submit directly to the Tumblr and have their content appear without being approved, while others had to be cleared by me. Students with Tumblr accounts had their names attach automatically, while other posts remained anonymous. Submissions were often poorly formatted, especially when students needed to compose more complicated posts (with links, multiple images, etc). I wound up having to re-format several student posts, particularly in the case where students posted a youtube link address, rather than having the option to embedded a video. These problems could have been avoided if they had access and training (see below) in the Dashboard feature. 2. Give Them a Tutorial I rather dumbly presumed that, hey, my students are all “children of the Net”. I thought they’d acclimate quickly to this interface just like I did, and they could google for help. This presumption was a mistake on my part—because there’s more than one way to skin a cat on Tumblr, there’s also more than one way to make an ugly post, or a post that’s accidentally all HTML code. I didn’t forsee that they needed to be taught how to “Copy Image Location” rather than a Google image site address, how to link text, even to double check the site to make sure their content loaded. In short, the site was a BIT of a mess because I didn’t anticipate that they needed to be taught basic technical web skills. In the future, I will require students to accept a member invite to the Tumblr, give a basic tutorial to Tumblr on the first day (with an instructional post for students who add the class late), NOT have a “submit” sidebar and require them to compose a technically correct post with a variety of content types (text, image, video are the most common). Barring my first-timer errors, I think Tumblr was a worthwhile addition to my class, has dynamic participatory potential, and I plan on using it in the foreseeable future. Open Questions 1. Privacy—Student and Instructor I’d originally set up the Tumblr to be password protected, but this was creating difficulties for some students that I didn’t have time to deal with, so I thought it easiest to just drop the password protection and make the whole thing public. However, I’m cognizant that students—and their writing—are identified by name. I’m not sure how to contend with this, and it wasn’t a problem I thought about when I threw the Tumblr together (not a topic really covered in traditional humanities pedagogy classes). I’m inclined to mothball this Tumblr because I didn’t take into account issues of student privacy, and try to come up with a more secure system for next time. Any thoughts? 2. Archiving If I use Tumblr for future classes, how do I manage these sites—does each class get its own secondary Tumblr (which could get voluminous fast)? Do all classes of the same course designation use the same Tumblr (presuming I’m not teaching multiple sections of a class in the same semester)? Is there any easy way for me to archive a Tumblr site for my own files, while deleting it from the net? For anyone who has used Tumblr for multiple classes, how do you manage these complexities? |

Archives

March 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed