|

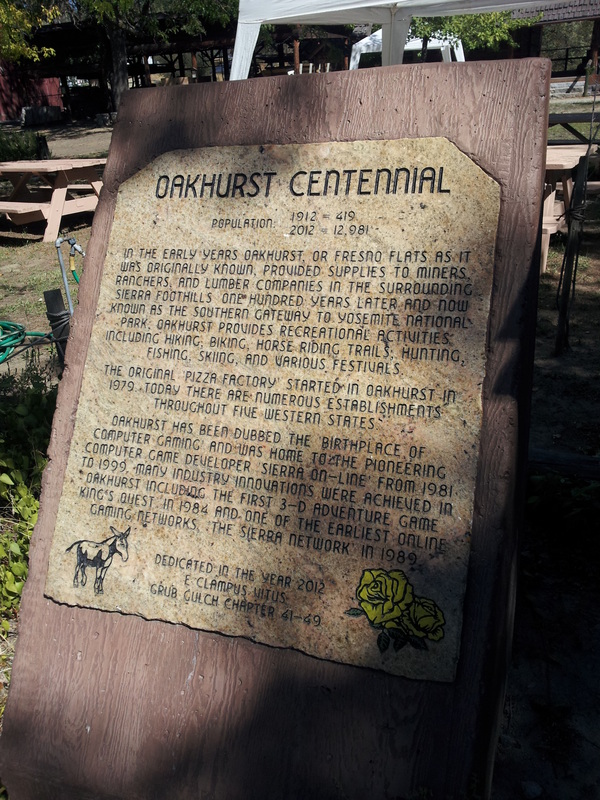

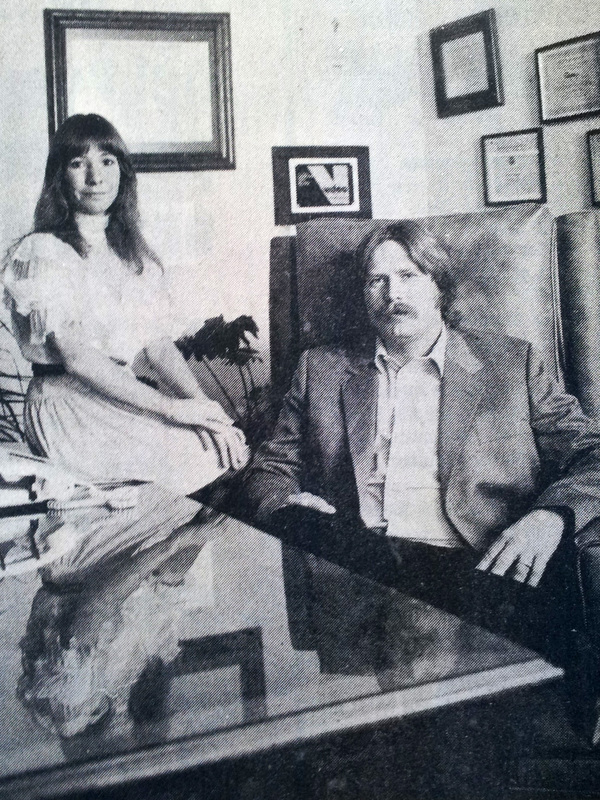

To celebrate the submission of my dissertation to my committee, I am posting an excerpt from the first chapter. I hope those of you who have followed my progress on social media or IRL enjoy this teaser for the project. I look forward to sharing more of it in the future. -Laine Chapter One: Emergences “In some adventures you are limited by the number of objects you can carry at one time. When it comes to a decision as to whether you should keep carrying an object that you already used, or drop it so you can get a new one, I would be inclined to drop it in order to be able to carry a new one.” —Roberta Williams “Winning Strategies for Adventures” The On-Line Letter, June 1981 Late in the summer of 2013, I traveled to Coarsegold and Oakhurst, California, a pair of towns separated by a seven-mile band of asphalt marked State Route 41, tucked away in the foothills of Madera County along the southern border of Yosemite National Park. On the last day of my trip, I drove out to Oakhurst's Fresno Flats Historic Park, a community heritage site established in 1975 in homage to the area's nineteenth-century Gold Rush roots. In a landscape rife with salt-of-the-earth history, these sorts of regional memorials dot and fleck every one-stoplight town along the highway. Most of them were founded in the 1970s and '80s, the boom years of civic pride in Madera County, when the middle-aged grandchildren of gold panners and loggers began gathering oral histories and commemorating landmarks. Yet, by 2013, these locales were mostly forgotten, the stuff of grade-school field trips and the occasional wedding reception. Those who had long served as the guardians of small-town memory, the founders of these dusty parks and ramshackle museums, were all thirty or forty years older now, their bodies too broken down to continue necessary repairs, their hands shaking and shivering as they leafed through archival documents, their memories shot through with forgetting. The Fresno Flats Historic Park's docents and guided tours had long since dried up; only a “caretaker” resided on premises during daylight hours, an old-timer sitting in an air-conditioned cabin who could hand you a pamphlet or give you directions. Mostly, I just saw people stop by to use the park's unlocked bathrooms. But if there was no docent to play warder to this park, to ensure I wasn't trying to jimmy my way across every locked door and sagging chain-link fence (which I certainly was), I did have to confront a very different kind of gatekeeper. A centennial plaque held empty court on the central axis of the park's sunburnt grassy entrance—what I suspected was faux marble mounted on faux wood. Dedicated by E Clampus Vitus, a regional fraternal order once founded to care for miners' widows, the plaque iterated Oakhurst, California's most defining testaments to national significance over the past hundred years. Most prominently, the town held a key location on the supply trails that once siphoned tools, liquor, and mules up to the northern gold mines and lumber sites leading in and out of Yosemite; second, Oakhurst was the founding location of Pizza Factory, a restaurant franchise boasting over one hundred establishments in five Western states; and lastly, the plaque dubbed Oakhurst “the birthplace of computer gaming.” Through the 1980s and '90s, Oakhurst and the smaller town Coarsegold had been home to Sierra On-Line, one of the most iconic and successful home computer entertainment software producers in the world. Co-founded by a curious husband-and-wife pair, Ken and Roberta Williams, Sierra found its fortune mostly in designing and distributing graphical adventure game software for the home computer market. Sierra would become one of the town's largest employers, alongside the Sierra-Tel telephone company and the county government. Up until the early 1990s, every box, every disk, every package was printed, formatted, and shrink-wrapped right in Oakhurst by the hands of self-declared “mountain folk.” Sierra On-Line was the reason I had traveled three thousand miles from New York City to get sunburnt and dehydrated twenty-two hundred feet above sea level. I'd come to this countryside to ask a question: what is video game history? Answers shift. In Coarsegold and Oakhurst, it seemed something best forgotten. There had been a soft promise, nearly thirty-five years ago, that a company like Sierra On-Line could turn the economic sinkhole of Madera County into a “Little Silicon Valley.” When Sierra moved most of its corporate operations to Bellevue, Washington in 1993, it left behind disgruntled memory and boundless rumor: Sierra had left because corporate taxes were too high, because they couldn't get a T1 line strung into Oakhurst, because relations were amiss at the top of the company chain. Double damage came in the late 1990s when the company was shuttered for good, closing up its remaining Oakhurst offices. After that, Sierra On-Line was just someone’s last paycheck. Yet, to the now-adult fans who teethed on Sierra's software in the 1980s and '90s, the company's material remnants—folded and boxed and sleeved by local labor but shipped to an audience worldwide—are objects to save, collect, cherish. These childhood memories are for sharing and endless reiteration. And there are other bodies, spaces, things. To the women of today's indie game scene, there's the hope of finding a history in Roberta Williams that reflects the history they lived but no one seems aware of—that, yes, women have always played games, and made them too. In the archives of the Strong Museum of Play, video game history is the mundane artefacts that clutter acid-free boxes: nameplates and buttons and broken awards. To the designers and employees I interview, it's a curiosity about why I care. It's a question of how long a floppy disk can hold its data before bit rot eradicates magnetic trace, and about how long Yosemite’s Half Dome will stand, a reminder of the thick temporality of stone. While the realm of armchair historians and amateur preservationists may swear to a video game history circumscribed by a heroic chronology of hacker heroes and coding wizards, “seminal games” and groundbreaking companies, tracking and tracing Sierra 'cross fields archival and literal has only confirmed to me the articulate queerness of our historical desires, of what we want history to do for us. The question of “what game history is” finds its answer in the doing, as this project is one that will take shape in the cluttered valley between history and historiography. The writing of video game history, despite its many participants, has been a fairly narrow field of action landmarked by a handful of monuments: Pong and the Magnavox Odyssey, Mario and Pac-Man, the alien death romps of Doom, the mesmerizing landscapes of Myst. Goldeneye, Grand Theft Auto, Wii Tennis. The ruins are real, and their importance inestimable—but they also cast shadows. In marking the map, they make it, they become what game history has been organized to show us. No book of video game history ever told me that Oakhurst, California was the “birthplace of computer gaming.” It probably is not. But what does that physical memorial make available to me, which I otherwise might not notice?

I believe: Sierra On-Line is the case that makes a mess of video game history. It makes good on Foucault's promise that “what is found at the historical beginning of things is not the inviolable identity of their origin; it is the dissension of other things. It is disparity.” My work herein is a media archaeological pressuring of several historiographic devices governing the structure and arc of what is taken as video game history. Articulating sites of disparity is a critically overdue maneuver in the unfolding historiography of the video game, a gesture countering the obviously problematic teleologics of much writing in the field. And it is a move that scales nicely beyond itself, to all the reasons video games are not just one component of a digital media landscape, but a condensation of digital media's most significant cultural and theoretical properties, from labor to materiality to transnationalist flows, global economics and mobile ubiquity to representation and virtual identity, down to design, distribution, the evils of e-waste. These are all part of a use-cycle of the global video game industry, a multiplicity which has no monolithic center, no representative feature, especially not once we formulate on planet-wide scales. Gaming is the first form of computational technology most of us ever handled—the first time, in many cases, a computer was ever “in our hands.” The level of convergence games enact with other media is a phenomena unto itself: games are constrained by no essential medium of transmission or reception, and can operate across digital and analog substrates. Games are neither experimental novelties nor thin amusements: they are definitive modes of mediation in the twenty-first century. The value of studying video game history should not be that it leads us back to games, but that it leads us somewhere else. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

March 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed