|

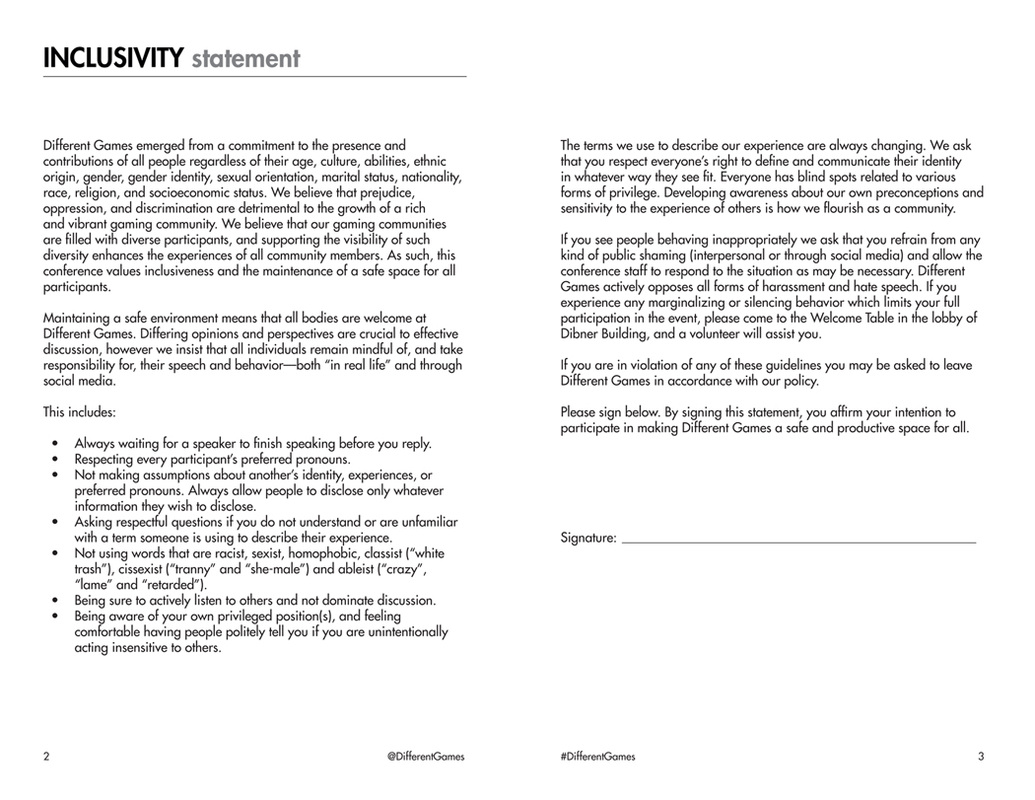

The recent weeks have been lush with excellent re-caps of the Different Games Conference, which I co-organized with Sarah Schoemann at NYU-PolyTech, April 26 + 27. Feedback has been overwhelmingly positive, and I’ve been really gratified to see that areas which bore more friction—especially issues around ableism and ableist language—have been summarize and assessed with grace and thoughtfulness (see Alison Harvey’s excellent summary/response here). Sarah and I have a lot to be proud. It’s been noted in several blogs and tweets that Sarah and I were accepting of criticism and concern, and made efforts to respond transparently to issues that arose. No one should underestimate the enormity of that challenge—of trying make choices carefully guided by one’s politics while you’re pulling off the most stressful event of your life, and you feel like your whole community is watching your every step. But our politics were what we started with, the one joint that carried us through the planning and managerial process. No matter how different our aspirations or intentions were at the beginning, the thing that fused this project together was that Sarah and I cared so deeply about making this a safe and inclusive conference. Much attention has been brought to our conference inclusivity statement: to the power and intention of its existence and its language, and the importance of the symbolic act of asking everyone to sign it. In this post, I want to detail some of this history of how Sarah and I came to make this document. More importantly, I want to highlight the critical contribution of our inclusivity consultant, Tim Johnston, who is largely responsible for the document’s success. Making a Start The idea for some sort of “safe space” statement came up while following the coverage surrounding the sexist language called out at Py-con by Adria Richards, which subsequently resulted in firings and death threats. As we knew this conference was bringing together a range of people with very different exposures to what it might mean to be “inclusive,” to value “difference,” and to foster a “safe space,” Sarah and I figured it would be good to spell this out somewhere on the website or program. Once the program design began in earnest, I started to try and draft it up. I’ve got plenty of experience with pedagogic and administrative writing, critical theory, and academic gender studies; Sarah is familiar with languages that emerge around skillshares, anarchist events, and queer community organizing. But as we passed this document back and forth, it just felt messy and unfocused. I scoured the internet for examples; university documents were all too vague and bureaucratic, while ones from community organizing didn't have enough of a professional glean. We knew this was a special event, and we wanted something that directly reflected the sensitivities of the conference. Asking for Help I felt surprised at how hard this was for me, and a bit embarrassed. I'd presumed a document like this would come easy. Frustrated, I turn my thoughts outside of myself: “Who in my community could help me with this? Who would be gifted at this?” That's how Tim Johnston became our inclusivity consultant.  Tim Johnston, Different Games Inclusivity Consultant Tim Johnston, Different Games Inclusivity Consultant Tim is a Ph.D. candidate at Stony Brook University in the Department of Philosophy. We'd met while getting our Women's and Gender Studies Graduate Certificates, and became close friends. Tim's dissertation focuses on affirmation as a philosophical concept and embodied practice, one especially important for queer bodies. What years of study and careful thought have wrought in Tim is a deeply internalized sensitivity to how bodies exist in space, and a powerfully analytic articulation of what is needed to help bodies feel safe. Far from abstract “ivory tower” theorizing, Tim applies these ideas to assess GLBTQ bullying policies, and concerns around inclusive space-making generally. Tim is a consultant-for-hire, and those interested in learning more about what he can offer your own events should visit his website. The proof is in the work. I sent Tim our sketchy paragraph. Tim spoke with me on the phone and prodded me to articulate why we needed this statement and what we were hoping it would accomplish. Given the Py-Con event, we were especially anxious about language issues, and how to express to everyone, in an open way, that we aspired toward specific affective goals as a community. What Tim passed back to us wasn't a list of demands, or a document intended to “get anyone” but rather a call to set an intention. Feel ok calling others out. Ask questions about things you don't understand. Be polite, make space, let's all be humane. Alot of the tenor of the piece rose from Tim's awareness that you don't build community by making people feel alien. Folks who may not “get” the statement needed to feel invited in as well. I think that's why the term “inclusivity statement” stuck; this community needed to hold all of us. Gathering the Team In keeping with the politics of the inclusivity statement, Sarah and I elected to hold an “inclusivity training” with all our potential volunteers a week before the conference. Tim served as our hand's on instructor during this time. He asked the volunteers to talk about what they hoped the conference could accomplish, and read through the document to ensure that everything was clearly understood. It should be noted that Tim was, among other things, uniquely responsible for the bulleted list of action points and the signature line. During the inclusivity training, he and the other volunteers pushed Sarah and I to begin the conference with a call to sign the inclusivity statement. “This isn't a legal document,” I recall Tim saying with a laugh. “But the symbolic act of signing it helps us set a goal.” Tim organized the experience in a way that made the best use of our time, and focused on the needs of our conference specifically. We were able to clearly explain to our volunteers that they were not “behavior police.” Tim offered tips on conflict mediation, should issues arise, and solicited questions and feedback from the volunteers themselves. This produced a valuable contribution—volunteers expressed uncertainty about Twitter use during the conference as a “snark backchannel” that might produce an experience in contrast to our goals. Tim led a discussion on how we might address this without making it seem like we're silencing social media use, and then we elected to add this material into the inclusivity statement itself. In conclusion, the statement worked because it was an expression of our own political desires for our event, we accepted our own limits in its making and drew assistance from others, and allowed it to be a dialectical creation with our volunteer staff, in a way that made us all feel more invested. It was empowering to write and present, and I would absolutely recommend the formation of such a document, in consultancy, for events where issues around difference and inclusion are particularly fraught. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

March 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed