|

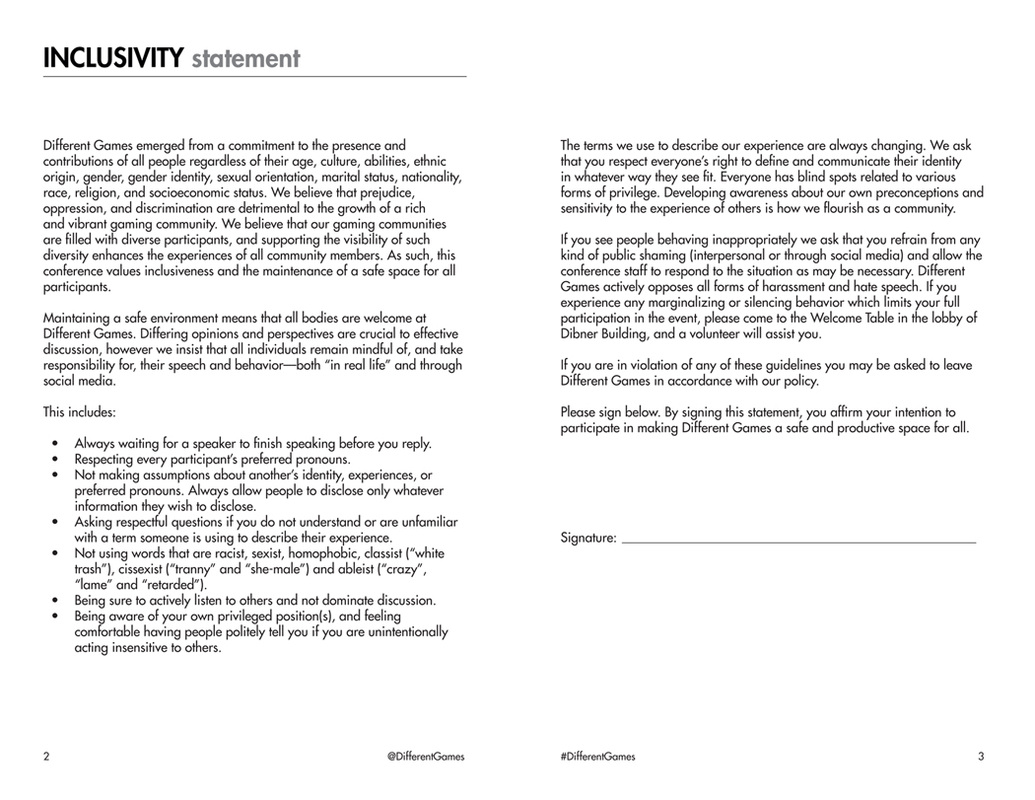

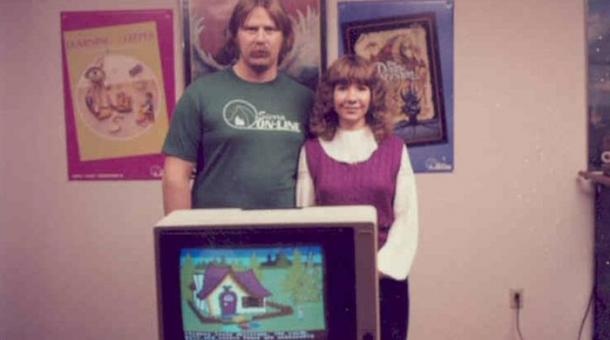

The recent weeks have been lush with excellent re-caps of the Different Games Conference, which I co-organized with Sarah Schoemann at NYU-PolyTech, April 26 + 27. Feedback has been overwhelmingly positive, and I’ve been really gratified to see that areas which bore more friction—especially issues around ableism and ableist language—have been summarize and assessed with grace and thoughtfulness (see Alison Harvey’s excellent summary/response here). Sarah and I have a lot to be proud. It’s been noted in several blogs and tweets that Sarah and I were accepting of criticism and concern, and made efforts to respond transparently to issues that arose. No one should underestimate the enormity of that challenge—of trying make choices carefully guided by one’s politics while you’re pulling off the most stressful event of your life, and you feel like your whole community is watching your every step. But our politics were what we started with, the one joint that carried us through the planning and managerial process. No matter how different our aspirations or intentions were at the beginning, the thing that fused this project together was that Sarah and I cared so deeply about making this a safe and inclusive conference. Much attention has been brought to our conference inclusivity statement: to the power and intention of its existence and its language, and the importance of the symbolic act of asking everyone to sign it. In this post, I want to detail some of this history of how Sarah and I came to make this document. More importantly, I want to highlight the critical contribution of our inclusivity consultant, Tim Johnston, who is largely responsible for the document’s success. Making a Start The idea for some sort of “safe space” statement came up while following the coverage surrounding the sexist language called out at Py-con by Adria Richards, which subsequently resulted in firings and death threats. As we knew this conference was bringing together a range of people with very different exposures to what it might mean to be “inclusive,” to value “difference,” and to foster a “safe space,” Sarah and I figured it would be good to spell this out somewhere on the website or program. Once the program design began in earnest, I started to try and draft it up. I’ve got plenty of experience with pedagogic and administrative writing, critical theory, and academic gender studies; Sarah is familiar with languages that emerge around skillshares, anarchist events, and queer community organizing. But as we passed this document back and forth, it just felt messy and unfocused. I scoured the internet for examples; university documents were all too vague and bureaucratic, while ones from community organizing didn't have enough of a professional glean. We knew this was a special event, and we wanted something that directly reflected the sensitivities of the conference. Asking for Help I felt surprised at how hard this was for me, and a bit embarrassed. I'd presumed a document like this would come easy. Frustrated, I turn my thoughts outside of myself: “Who in my community could help me with this? Who would be gifted at this?” That's how Tim Johnston became our inclusivity consultant.  Tim Johnston, Different Games Inclusivity Consultant Tim Johnston, Different Games Inclusivity Consultant Tim is a Ph.D. candidate at Stony Brook University in the Department of Philosophy. We'd met while getting our Women's and Gender Studies Graduate Certificates, and became close friends. Tim's dissertation focuses on affirmation as a philosophical concept and embodied practice, one especially important for queer bodies. What years of study and careful thought have wrought in Tim is a deeply internalized sensitivity to how bodies exist in space, and a powerfully analytic articulation of what is needed to help bodies feel safe. Far from abstract “ivory tower” theorizing, Tim applies these ideas to assess GLBTQ bullying policies, and concerns around inclusive space-making generally. Tim is a consultant-for-hire, and those interested in learning more about what he can offer your own events should visit his website. The proof is in the work. I sent Tim our sketchy paragraph. Tim spoke with me on the phone and prodded me to articulate why we needed this statement and what we were hoping it would accomplish. Given the Py-Con event, we were especially anxious about language issues, and how to express to everyone, in an open way, that we aspired toward specific affective goals as a community. What Tim passed back to us wasn't a list of demands, or a document intended to “get anyone” but rather a call to set an intention. Feel ok calling others out. Ask questions about things you don't understand. Be polite, make space, let's all be humane. Alot of the tenor of the piece rose from Tim's awareness that you don't build community by making people feel alien. Folks who may not “get” the statement needed to feel invited in as well. I think that's why the term “inclusivity statement” stuck; this community needed to hold all of us. Gathering the Team In keeping with the politics of the inclusivity statement, Sarah and I elected to hold an “inclusivity training” with all our potential volunteers a week before the conference. Tim served as our hand's on instructor during this time. He asked the volunteers to talk about what they hoped the conference could accomplish, and read through the document to ensure that everything was clearly understood. It should be noted that Tim was, among other things, uniquely responsible for the bulleted list of action points and the signature line. During the inclusivity training, he and the other volunteers pushed Sarah and I to begin the conference with a call to sign the inclusivity statement. “This isn't a legal document,” I recall Tim saying with a laugh. “But the symbolic act of signing it helps us set a goal.” Tim organized the experience in a way that made the best use of our time, and focused on the needs of our conference specifically. We were able to clearly explain to our volunteers that they were not “behavior police.” Tim offered tips on conflict mediation, should issues arise, and solicited questions and feedback from the volunteers themselves. This produced a valuable contribution—volunteers expressed uncertainty about Twitter use during the conference as a “snark backchannel” that might produce an experience in contrast to our goals. Tim led a discussion on how we might address this without making it seem like we're silencing social media use, and then we elected to add this material into the inclusivity statement itself. In conclusion, the statement worked because it was an expression of our own political desires for our event, we accepted our own limits in its making and drew assistance from others, and allowed it to be a dialectical creation with our volunteer staff, in a way that made us all feel more invested. It was empowering to write and present, and I would absolutely recommend the formation of such a document, in consultancy, for events where issues around difference and inclusion are particularly fraught. The past two weeks have been a bit dizzying--full of excitement and possibility and adventure within and beyond the walls of the academy. Here's some recap, and preview of up-coming stuff I'm involved in. SCMS: Society for Cinema and Media StudiesThis year's Chicago conference was a time of great connection and re-connection. The media archaeology panel was a pure success; I've been encouraged to flush out my feminist critique of media archaeology and pursue publication. As a grad student, this was feedback I very much needed--I operate in a department largely unaware of the emergent trends in media studies, and my engagement with the field outstrips that of my advisor. Demoing this work for folks who are "stakeholders" in this conversation, and having them socially "sign off" on the project was just the POV I needed to confidently move forward with what I deeply, naggingly know is work I have to do. Other academic highlights included the "Debugging Terminology in Video Game History," which previewed some of the great work forthcoming from Henry Lowood and Raiford Guin's co-edited Game History Lexicon, the Platform Studies Roundtable (do we have any agreement on what "platform studies" means? absolutely not), and the Digital Networks panel, which included Patrick Jagoda's breathtaking presentation on network aesthetics. As the Sounding Out! blog reported, the terrain of the conference is shifting; new domains in media studies--sound studies, materialist media studies, videogame studies--are capsizing the long-standing primacy of film (and even television) at this conference. Many of the young scholars I spoke with--ABD grads and jr. faculty--are curious to see if SCMS will be able to hem these increasingly divergent interests together, or if there may be some need for media studies to strike out on its own. Where IS the big-league media studies conference that isn't a tack-on to some other discipline? (as we experience at SCMS, 4H, MLA, ACLA, ICA, etc.) Marketplace TechReport InterviewWhile at SCMS, my Marketplace Techreport interview aired on NPR! It was an aweing experience to meet the famed and insightful David Brancaccio in this context. David has been carrying a beat on "Who is Tech?" and paying special attention to the issues around sexism in the game industry. My report was, in part, to provide alternative histories that can help us be more thoughtful about how we frame these debates today. Different GamesDifferent Games is fast approaching! This conference is the first of its type organized around issues of difference, diversity and intersectionality in game design, game scholarship and game criticism. The conference was created by Sarah Schoemann of NYU-PolyTech, and is co-organized by myself and Sarah (with the assistance and input of many!). Different Games will be hosted by the Technology, Culture and Society Department at Poly, April 26-27. We'll have tracks of academic papers, design presentations, a game arcade, workshops, and breakouts. Our keynotes are Mary Flanagan and Celia Pearce, and the event will also include presentations by Anna Anthropy, Mattie Brice, Adrienne Shaw, Raiford Guins, Nick Fortugno, and lots of other ballers, big and small. The schedule is still pending, but should be out soon. This conference could not have been better timed to be in sync with current events in the game industry. Personal Best @ NYU Game CenterAs part of an effort to build excitement about Different Games, and also bring attention to feminist issues in game scholarship, Sarah Schoemann (TCS, PolyTech) and Toni Pizza (NYU, Game Center) have been working together on a lecture series called Personal Best: A Series on Feminist Game Design Practices. Personal Best first featured Jessica Hammer, speaking on designing games for Ethopian teenage girls. I'll be the second figure in Personal Best, speaking on Roberta Williams (surprise!). There will be new content here, compared to my Provost Talk--including info on the larger West Coast game industry Sierra was a part of, and a more theoretical examination of why women's play has been left out of early game history. Full verbage below; Facebook invite here. Talk Title: Before We Were "Gamers": Roberta Williams, Sierra On-Line and How We Write Women into Video Game History

Personal Best is excited to welcome our second speaker, Laine Nooney whose lecture will cover some of the founding hits of Roberta Williams' game design career and offer insight on how Williams' understood her own design practice, put in the context of Sierra On-Line as an important company of the 1980s home computer software boom. Furthermore, the contributions of Williams will be framed within the larger context of video game history, and focus on how women like Roberta Williams aren't simply "additions" to a historically male gaming narrative but could actually challenge what we understand the history of games to be. This week hundreds of film and media scholars will descend upon Chicago for the 2013 Annual Meeting of The Society for Cinema and Media Studies. This is my second year in attendance, and I'm especially looking forward to this year's conference. I've organized a panel on media archaeology, and I'll be giving my talk on feminist materialism, Roberta Williams' Mystery House, and an approach to materialist method I delinquently term "media gynaecology." I can't speak highly enough of the folks participating on the panel, and I think we're going to engage a valuable--and necessary--conversation on methodology within media archaeology. Below is the information on our talks, and the longer panel abstract.

Panel Title: New/Media/Archaeologies: Extensions and Interventions in Media Archaeology Panel Number: F11 Chair: Laine Nooney | Stony Brook University Rory Solomon | Parsons the New School for Design “Software Stratigraphy: Media Archaeology of/as the Stack” Shannon Mattern | The New School “Echoes and Entanglements: A Sonic Archaeology of the City” Laine Nooney | Stony Brook University “Materialist Methods for Mystery House(s): A Feminist Media Archaeology of Early Video Games” Jacob Gaboury | New York University “An Archeology of Uncomputable Numbers: Queer Media History” Panel Abstract: Over the past 20 years, media archaeology's emphasis on non-progressive media histories, dead and failed media, and media materialism has refreshed the theoretical domains of media studies. Scholarship in media archaeology has long been united by a methodological focus on the primacy of the technological medium itself, rather than its representational content. However, these methods, by outrightly rejecting questions of discursivity, subjectivity and political economy, produce their own academic difficulties. The anti-hermeneutic tradition of media archaeology has produced a body of scholarship that often leaves unaccounted the ghostly or immaterial components of media studies that do not leave technological registers in our material world. This panel re-assesses the intersections of objects, subjectivities and environments that typically lie beyond media archaeology's reach, extending media archaeological methods across disciplinary boundaries. Rory Solomon offers a programmer-oriented view, complicating the notion of a purely non-discursive technical substrate using the software model of the “stack.” The “stack” illustrates that operative layers always exist above and below any substrate; methods are best imagined as “both/and” rather than “either/or.” Shannon Mattern productively confuses the distinction between media archaeology and archaeology “proper,” in an effort to address the very literal “digging” required to write a history of urban sound. Mattern insists media archaeology should learn from actual excavation, as material practices are all the more significant when one must unearth forms of mediation that themselves have no physical instantiation. Laine Nooney continues to focus on material context, arguing that media archaeology remains deeply gendered when scholars privilege objective analyses of media objects that forgo cultural and human materiality. Nooney intersects feminist materialism with media archaeology to highlight the largely “invisible” female affective and material labor at work in video game history. Jacob Gaboury locates a queerness in media archaeology demanding further attention to identity-based critiques. Gaboury suggests that media archaeology's attention to failed, glitched and re-occurring processes dovetails with queer theory's turn toward a politics of failure and anti-sociality, and reads computer history against its grain to offer a queer alternative to the telos of “successful” communication. |

Archives

March 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed