|

Please Note: All images were taken by me and are available courtesy The Strong Museum of Play. No images herein may not be copied, reposted, reblogged or transferred to another site without my notification and consent. The first corporate sale Doug Carlston ever made was on March 7, 1980, in the amount of $299. He had worked as an attorney, an economist and a dog breeder, volunteered in the Peace Corps and written a book on Swahili. But this nominal sale would take Carlston on a truly life long career, as one of the world’s first independent home computer software moguls. The sale comprised 30 cassettes of Carlston’s TRS-80 space strategy game Galactic Revolution, 10 cassettes of his sequel Galactic Trader, and 10 copies of the trilogy capstone Galactic Empire (5 on cassette and 5 on disk), mailed to a purchaser merely documented on a sales record sheet as “Program Store.” The games were sold under the company name Brøderbund, the Swedish word for “brotherhood.” It was an apt term: Brøderbund was founded by both Doug and his brother Gary (who’d been pried away from his job as a Swedish women’s basketball coach). Their first profit would come four months later, in the amount of $2023.97. Within a year, the brothers would be joined by their sister Cathy, who worked as a buyer of “women’s moderate coordinates in larger sizes” at Lord and Taylor before taking over as head of marketing at Brøderbund. Together, this family built a company of “refugees from other professions,” and published a slew of historic games: Choplifter, Loderunner, The Print Shop, Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?, and Myst. They were, as Steven Levy put it in Hackers, one of “the fastest risers of dozens of companies springing up to cater to new computer users,” alongside now canonical Sierra On-Line and the utterly forgotten Sirius Software (265). The sales record sheet mentioned above is one of several “first” documents which were carefully, considerately saved by Doug Carlston, and are now formally preserved as part of the Brøderbund Software, Inc. Collection held at The Strong Museum of Play in Rochester, NY. This collection, comprised of 14 boxes of materials, encompasses over twenty years of corporate documentation from Carlston’s own business files. I reviewed this collection during a 2-week research visit at The Strong this past January (this was my second visit, and this time I was the generous recipient of a Strong Research Fellowship). I consider The Strong, and its internal research repository, The Brian Sutton Smith Archive and Libraries of Play, to be the nation’s leader in video game archival practice. This is not just because they have a massive playable collection of original hardware and software, but because they understand games themselves as no more or less important than the people, processes and contexts that bore them. This was a lesson powerfully driven home during my visit, as I sat in the Museum library and held Carlston’s sales record sheet in my hands. Doug Carlston was the kind of man who saved things. What he saved tells me nothing about the importance of Carmen Sandiego or Loderunner; it will fill no brightly colored book about the triumph of video games and their explosion across America. It’s a quiet fact that requires contemplation. So Doug Carlston was the kind of man who saved things. Not everything—he was no hoarder—but there was a logic and a sensibility to this record keeping. Every filing cabinet contains the pattern of a history—not just in the documents stored within but through the nature of their organization. In the upper right hand corner of many of Carlston’s documents, I could find a handwritten note: “File,” sometimes with a directive for what content area folder the document should be dropped in or who else should see the document. It suddenly gave me a glimpse on a habit of work that I have never, personally, had to engage: documents would come to Carlston’s desk, be reviewed and annotated. What then? Many needed to be saved, so Carlston wrote “File” and—it’s not a leap to fill in this blank--turned them over to his secretary for filing (if Carlston did his own filing, which a man of his position certainly would not, he would not have needed to note where he wanted the files placed). This tells me something about a man: not just that he saved things, but that he believe in the necessity of documentation, precedent, record-keeping, evidence. After a moment it’s the kind of detail that gels neatly with Carlston’s background as a Harvard trained lawyer. The reason I’m so struck by Carlston’s file-keeping, as a historian, is because I spend much of my research time analyzing the behavior, impact and company structure of a man who could be imagined as Carlston’s opposite: Ken Williams, President and CEO of Sierra On-Line. It’s a pleasurable irony that The Strong holds collections on both companies—the first time I visited The Strong, it was to explore their newly acquired Ken and Roberta Williams Collection in 2011. As a pair, the Williams collection and the Carlston collection offer the opportunity for a useful comparative study. Both companies began in 1980 producing games and other software for the Apple II, both presidents had no prior experience in business, and both companies became titans of the early microcomputer software world. Both would survive the economic shakeouts that took down most of their competition, both would produce some of the most significant, iconic software ever made for home computers, and both companies would last under the direction of their founding presidents for almost two decades (both companies were bought out and acquired by the late 90s, Sierra by CUC and later Havas, and Brøderbund by The Learning Company). But Ken Williams is not Doug Carlston, and the powerful distinction of their personalities and companies is to some degree captured in their comparative Collections. The Ken and Roberta Williams Collection is almost entirely comprised of front-of-the-house materials and marketing items: copies of their consumer magazine Interaction, publicity headshots, newspaper clippings, annual reports, press releases. Another category of objects I would classify as personal mementos: awards, gifts, framed fan letters, even Ken Williams’ office doorplate. The small sampling of design documents in the Collection is solely Roberta’s, and all documents she either personally produced or interacted with. The Collection is, on the one hand, very much about company image, and on the other, deeply personal. I can imagine Ken Williams unscrewing and sliding the nameplate off his door on that final day of his presidency, unclipping his name tag, lifting his pictures off the office wall, and saving these things for the same reason I still own my undergraduate ID from 2004: because these objects do some of my remembering for me. By all accounts I’ve gathered, Ken Williams was not a manager or businessman in Doug Carlston’s sense—he was not a man to take a moment and neatly pencil “File” on top of a document. People remember his office as characteristically cluttered, his management style as occasionally unpredictable, and he was often gripped by an overwhelming drive and technological imagination. Williams was future-leaning, as one interviewee pointed out to me. Why nurse what just happened (as documentation does) when you could be running ahead? And what all of this amounts to is a phenomenal gap in the archive expressive of character and illustrative of how an individual might imagine their relationship to history: The Ken and Roberta Williams contains no internal documentation. It is silent on the subject of how the sausage got made at Sierra. In contrast, the Brøderbund Collection is full of internal newsletters and memos, company profit and loss sheets, minutes from the Board of Directors, revised org charts—hundreds if not thousands of pieces of paper explaining how a company like Brøderbund actually functioned. I cannot, similarly, understand Sierra On-Line in such a way from materials left behind by its founders. In fact, Carlston’s record keeping was so thorough, I found more internal documentation about Sierra On-Line in the Brøderbund Collection that I did in the Ken and Roberta Williams’! Case in point, a most magnificent find: Sierra On-Line’s October 1986 Company Profile and Business Plan, as well as a 1987 Company Profile related to their proposed IPO (which would fall through due to the 1988 stock market crash; the IPO finally happened a year later in 1989). I confirmed the authenticity and context of these documents during a recent interview with Sierra’s 1980s Chief Financial Officer, Ed Heinbockel. The 50-some page 1986 Business Plan, in particular, was prepared by Heinbockel for a Board of Directors meeting, in an effort to aggressively restore the Board’s faith in Sierra’ profitability (and included some cute drawings by Space Quest's Mark Crowe!). Why in the world did Doug Carlston have this document in his records? Carlston and Williams shared a respectful friendship since their early days in the Apple II computer software scene, and Carlston was sometimes invited to Sierra’s strategy retreats. It’s possible that Ken Williams wanted Carlston’s opinion. Alternatively, these documents could have made their way over to Carlston during the early conversations about a once-anticipated late 80s Sierra-Brøderbund merger, but the annotated date in the top corner, “12/1”, lacking a year, suggests Carlston received the document in December 1986—well before the merger was even an idea (at least as far as I know).

The first researcher to truly crack into Brøderbund Collection will have a dissertation-defining gold mine on their hands—this Collection will likely comprise the extent of our archivally-based knowledge of the economics and development of the home computer software industry. And it's significant that such documents have been saved, as personal memory and fan obsessionalism increasingly proves a poor foundation for our historical knowledge of the video game medium. Brøderbund and Sierra On-Line are arguably comparable companies in terms of historical significance. Yet while Sierra fans have produced countless websites, a Facebook page, independent book projects and a twice-botched documentary, no citizen historians or fan communities have shown much interest in collecting and organizing the history of Brøderbund. Brøderbund never had the affable glossiness and friendly company demeanor that Sierra excelled at; Brøderbund’s public relations communications had the vibe of a corporate newsletter. It was also a point of business strategy that Brøderbund served most successfully as a publisher for the work of out-of-house programmers, whereas Sierra piloted a largely in-house business, and turned its programmers into software stars. Furthermore, much of Brøderbund’s significance has been overlooked because some of its best work was home productivity or education software, like Print Shop, rather than games. But in the long turning of history’s screw, the “memorability” of Sierra is what has caused it to be better remembered, and consequentially, more discussed and emphasized within academic, professional and lay communities. What Doug Carlston’s meticulous, rich body of documents makes clear is something I’ve strained to point out before: that the history of games is much broader than “games,” and sometimes the game is the least important thing. What is disclosed within these boxes and folders is corporate history, economic history, technological history, labor history. It gives us, better than any “killer game,” a vision of what the world was like when the age of the microcomputer dawned—and should impress upon us all the more respect and appreciation for those sometimes sloppy, sometimes thorough individuals who shepherded it into being.

1 Comment

On December 2, 2014, I published "The Odd History of the First Erotic Computer Game" over at The Atlantic. This maybe wasn't the most normative thing for a young postdoc to do with their time--but padding my CV couldn't quite compare with the constructive fun, wide reach, and challenging process of writing for a popular audience. And it's a rare pleasure to see something you write get shared over 1600 times (apparently that's 160x more than the average journal article is ever read).

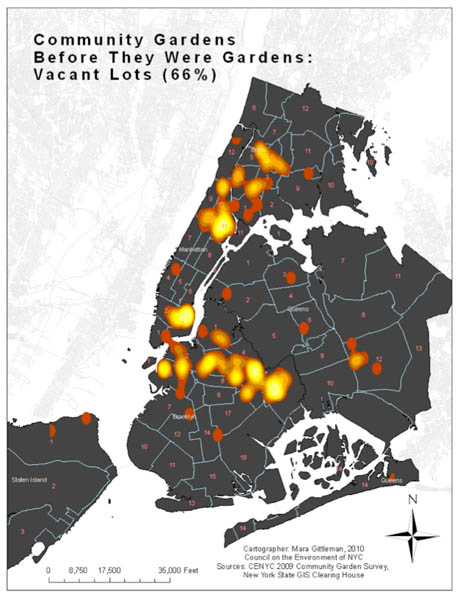

Since that piece went live, a funny thing has happened: several faculty and grad students have dropped me emails asking for advice on how they too could maybe write for a popular audience. It's easy to forget that--for all that academic training--communicating with journalists and editors, and writing for the educated masses, actually takes some reframing of perspective and and disciplinary behaviors. In fact, writing and speaking for a popular audience has taken a damn good bit of unlearning what grad school and the academy has taught me. So! As I've been answering this question alot for friends and colleagues, I thought I would just compile the advice I've been giving out and post it here for everyone's benefit. No guarantees implied, but hopefully you'll find this a helpful place to start. 1. Whenever Possible, Flex Your Network to Find a Point of Contact (Get a Network) Even imagining that I could write for The Atlantic would have been much more difficult if I hadn't had a friend who is a journalist who was able to give me a direct introduction to The Atlantic's Tech Editor at the time. It was actually a conversation we'd been circulating around for months, when we would run into each other at events. I felt very intimidated by the idea of writing for a popular press, and her intermittent encouragement went a long way. Obviously connections like these are harder to assemble (or outright impossible) if you don't live in a major metropolitan area. But you'd be surprised what asking around does. Maybe someone's brother or college roommate or old LiveJournal friend works in a field or for a venue you're interested in. Think out loud, don't limit your professional contacts to academia, and know nothing bad comes from asking for what you want. Also, lots of academics have pursued alt ac careers in journalism; maybe spend some time figuring out who those crossover folks are, and how you can be of service to them. And the worst case scenario? You do a cold pitch. See below. 2. Get out of the academic rejection model mindset Peer review, job searches and conference submission can make a meat grinder of self-esteem. We're conditioned to believe our ivory tower gatekeepers want to dislike your work, so they move quickly to the next application. Dr. Karen Kelsky even has some great wisdom on coming to grips with this reality of academic employment. I once explained this reality to a friend who was an actor. She told me the audition process couldn't be more different. "They want to love you. They want you to come in and be the person who makes their play come alive." (It doesn't mean you'll get the part, but still.) It was a powerful conceptual shift. I've come to learn the online journalism world has a touch of this too. Any major outlet has to produce so much content, every day, over and over again. They want to like your pitch. They want you to be the next smart person to make their life a little easier. This isn't the stern face of peer review, and there's no cruel hierarchy games here. 3. Act like a professional, not an academic Academics are prone to wordy emails, CV recitations for intros, and verbose explanations (my inbox is proof!). Especially if you're making that cold pitch, avoid overburdening the first point of contact. Keep intros succinct and get directly to the point. I would recommend that the opening inquiry email contain 3-5 sentences on the idea, and ends with something like "If this sounds like something that would be at home at [this venue], I'm happy to expand this into a formal pitch." However, do your due diligence: some sites have very specific directives about how they want pitches to be made or submitted, so look around on the website first. From there, it's just feeling out the relationship with the editor. I wouldn't expect a pitch to go over 2 paragraphs (mine didn't), but your editor knows best. 4. Be clear with yourself about the "big idea" and what you can accomplish A popular press venue is not a space to make academic arguments--no matter how dashing that argument may be. You can't use footnotes or cite references. Just own your knowledge and have a big, juicy idea. If there's a subtle point you want to prove, I always think it's sexier to show rather than tell. I've also learned that online writing favors smaller paragraphs and shorter sentence structure. In most cases, it's wise to take your editor's notes and corrections--they actually do know more than you in this arena. My friend in journalism, who I mentioned earlier, gave me some nice perspective on how to think about the audience and the writing: at the end of the day, you're giving someone a provocative, new topic to discuss with their friends at brunch. That doesn't mean the work is shallow. It means you have to be an ally to your reader, and create an inviting space for them to explore. Go forth and have readers! Ello made the rounds through my Facebook feed yesterday. I had the privilege of receiving an invite from a friend a few weeks ago, so I was in the lovely position to hand out invitations and watch my friends populate the left-hand grid of circles, arriving one-by-one like citizens new to a town. The earliest adopters among my friends are those I think of as social media old skoolers—in other words, LiveJournalers. That was the comparison they frequently made--that they felt like they were back on LiveJournal. I had a LiveJournal, like everyone did in those brutal early aughts, but was never a dedicated community member. I described my ello experience as like a community garden. Another word that felt apt: it is humane. I’m not speaking of the user interface, which is still a bit fraught and jerky, a little too minute (and I’ve already endured far too much complaint about the body font). I’m speaking of ello’s speed and mood. The sparse typeface, ample leading between returns, considerate white space, simple shapes—it feels manageable and pleasant. My friends write longer, and more meaningfully, than on Facebook, and it lacks the bratty 4chan-ism of Tumblr. Even that trouble UI slows you down, makes rapid posting tiresome. Cumulatively, ello creates a much needed sensibility of repose in an otherwise frenetic social media environment. Come here, tend your garden, look at my garden, let’s chat, and then let me leave. All of this, of course, could just be a by-product of scale. Right now I only have 16 people as Friends and 6 people as Noise. What happens when that number becomes 50, 100, 200? What happens when too much is happening on my feed? What happens when they inevitably need to monetize the space? Will ello prioritize maintaining that sense of poise which I think is its greatest asset? We often treat our media as all good or all bad—either its running us, or it’s the next step on the path to our transhumanist destiny. I prefer Marshall McLuhan’s formulation of media effects (and affects!), which is that for every sense a media extends, it also amputates something else. What we’ve struggle with since the emergence of digitized social media networks is quickly they consume our lives and reshape everything in their image. When I think of this in McLuhan-esque terms, this is a problem of extension and amputation. Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr—they extend us far and often amputate too much. What we’ve need for a long time isn’t an etiquette for social media, but practice, as Western networked humans, at dilating between the plunge and the withdrawal. As a species, we are simply untrained at this, and our technology designers are often drunk on technology’s own mysticism—giving us more integration, content and volume when we really just need is something more moderate, better designed.

And many of us have been unhappy with these forms of social media, especially Facebook, for a long time. Ello is a social network informed by many things we’ve wearied of in social networks—endless feeds, constant communication, the politics (and often clunky methods) for following but not following people you have to follow but may not like. Ello feels like a space not built for over-extension. Social networks like Facebook never had the chance to get these things right because they, in some sense, invented the problem. It’s not their’s to solve. This, I think, is what gives the space for ello to plot out its own parcel of land. Where this is going is hard to predict, but suffice to say: I like the gesture. |

Archives

March 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed